Authors:

Carlos Giraldo, Chief economist – FLAR.

Iader Giraldo, Principal economic researcher – FLAR.

Pablo Ruiz, Research assistant – FLAR.

Valeria Saldaña, Research assistant – FLAR.

The global economy is undergoing a reconfiguration process that is characterized by growing geoeconomic fragmentation, which is defined as the tendency for trade, investment, and global value chains to divide into geopolitically aligned blocs. This phenomenon, which is distinct from deglobalization, is driven by state-led strategies aimed at reducing critical dependencies and strengthening economic security (Blackwill & Harris, 2016). This fragmentation presents both challenges and opportunities for Latin America, depending on the region’s ability to adapt and position itself strategically.

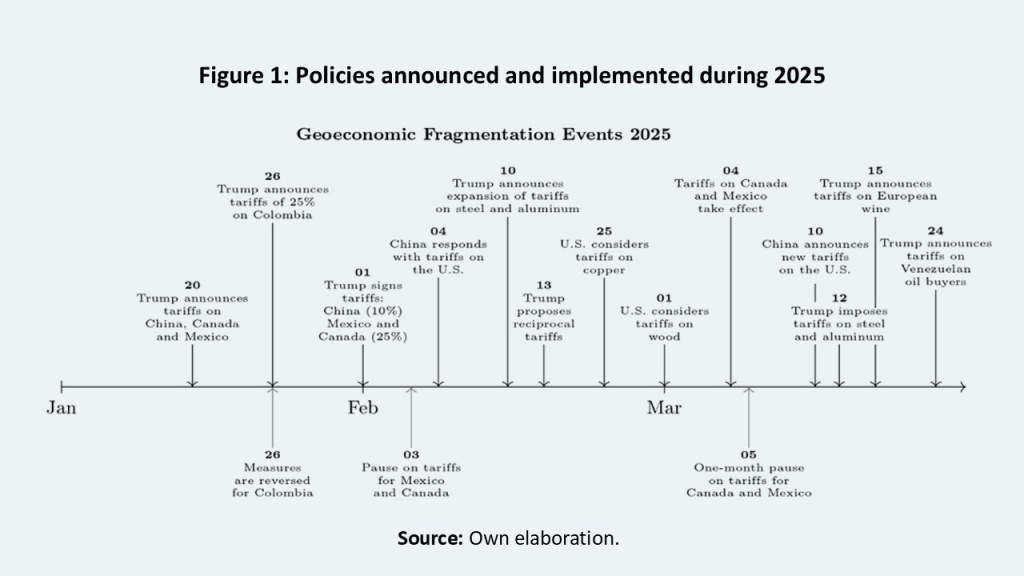

Several recent events have acted as catalysts for this process. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities of global supply chains, while the war in Ukraine, which began in 2022, intensified energy and trade tensions, accelerating “nearshoring” and “friendshoring” strategies in major economies. By 2025, the trade stance and the prioritization of national interests in U.S. foreign policy have reinforced the use of protectionist measures, such as the imposition of tariffs and the prioritization of bilateral trade over multilateralism (Figure 1).

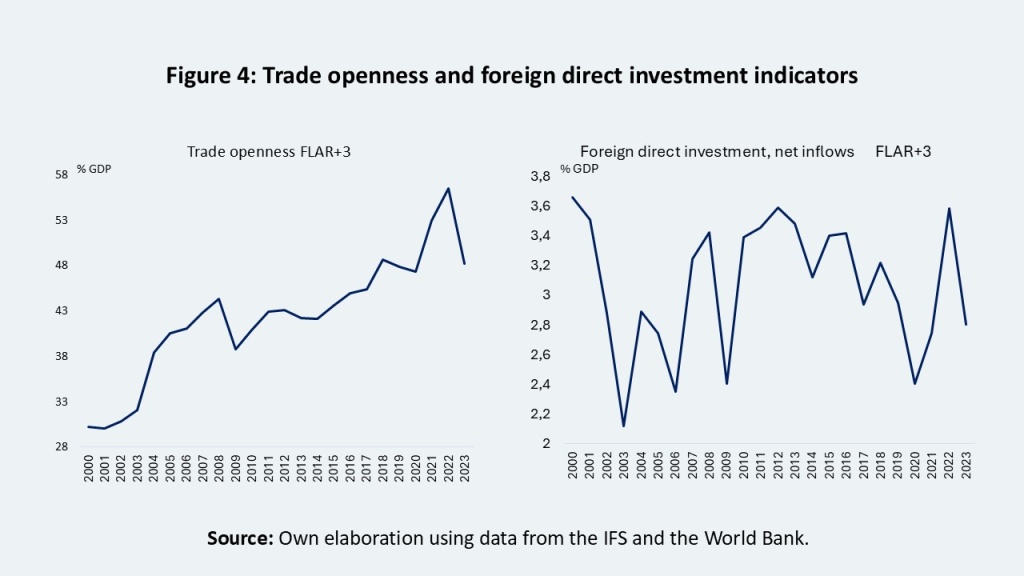

In the current global context, FDI in the region could face significant distortions and challenges due to the growing concentration of capital in geopolitically aligned countries (IMF, 2023). Since many of these flows are directed toward extractive sectors, many Latin American countries must manage not only the volatility of commodity prices—closely linked to economic stability and social well-being (Balakrishnan et al., 2021)—but also uncertainty regarding external financing and the sustainability of their growth models.

However, fragmentation also presents opportunities. If countries in this region adopt a neutral stance and position themselves as connectors between economic blocs, they could benefit from shifts in trade and FDI flows. However, achieving this goal would require structural reforms, infrastructure improvements, and greater logistical efficiency to manage these interactions.

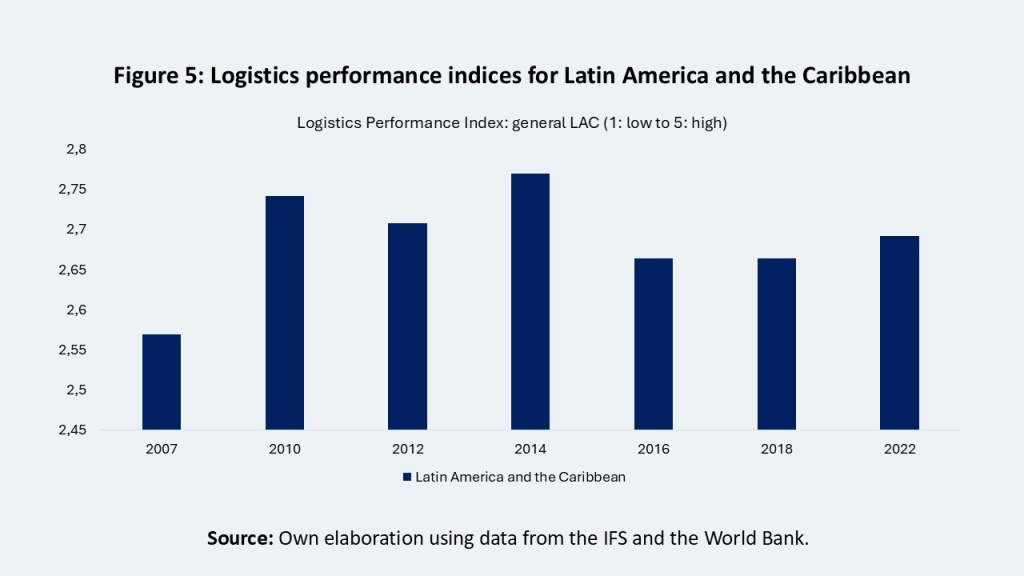

In this context, the region still faces significant constraints in terms of logistical capacity and trade openness, which hinder its integration into global and regional value chains. Scholars such as Machado & Moreau (2024) have emphasized a region’s critical structural deficiencies, which are linked to infrastructure and customs policy challenges. For example, a region’s poor performance in indicators such as the logistics performance index (see Figure 5) highlights the need to overcome difficulties related to customs procedures, infrastructure, organizational quality, and operational capacity to enhance global competitiveness.

References

Balakrishnan, R., Lizarazo, S., Santoro, M., Toscani, F., & Vargas, M. (2021). Commodity cycles, inequality, and poverty in Latin America. IMF Departmental Papers. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/DP/2021/English/CCILAEA.ashx

Blackwill, R. D., & Harris, J. M. (2016). War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1c84cr7

International Monetary Fund. Research Dept. (2023). Chapter 4 Geoeconomic Fragmentation and Foreign Direct Investment. En World Economic Outlook a Rocky Recovery. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400224119.081.CH004

Moreau, F., & Machado, R. (2024). The Dynamics of Trade Integration and Fragmentation in LAC. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2024/12/14/The-Dynamics-of-Trade-Integration-and-Fragmentation-in-LAC-559484