Authors:

Carlos Giraldo, Chief economist at Latin American Reserve Fund – FLAR – cgiraldo@flar.net

Iader Giraldo, Principal economic researcher at Latin American Reserve Fund – FLAR – igiraldo@flar.net

Jose E. Gomez-Gonzalez, Department of Finance, Information Systems, and Economics, City University of New York – Lehman College, Bronx, NY, USA. / Visiting Professor, Escuela Internacional de Ciencias Económicas y Administrativas, Universidad de La Sabana, Chía, Colombia – jose.gomezgonzalez@lehman.cuny.edu

Jorge M. Uribe, Serra Húnter Fellow, School of Economics, Universitat de Barcelon, Barcelona, Spain – jorge.uribe@ub.edu

In the current landscape of financial economics, the concurrent risks of default and depreciation in emerging markets, particularly within Latin America, have re-emerged as fundamental areas of study. This blog post goes through our recent research, which explores how shifts in the US term spread influence these twin risks—default and depreciation—in five key Latin American markets: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico.

Our study builds on the established premise that greater sovereign risk correlates with heightened depreciation risk (Della-Corte et al., 2022). Conversely, expectations of currency depreciations increase the likelihood of defaults (Bernoth and Herwartz, 2021). This interconnection, often called the ‘Twin Ds’—default and depreciation—is crucial for understanding the financial dynamics within emerging markets. As documented by Reinhart (2002) and further analyzed by Na et al. (2018), the optimal policy response to adverse economic shocks often involves both defaulting on debt and devaluing the currency to manage economic downturns effectively.

According to these authors’ framework, when confronted with a series of adverse outcome shocks leading to default (due to limited commitment), governments are inclined to devalue the local currency to mitigate the impact on real wages. By doing so, governments can offset the downward pressure on labor demand resulting from the contraction in domestic absorption caused by these negative shocks.

Building on the insights of Na et al. (2018), we posit that this original sequence of negative shocks could be due to changes in expectations regarding global economic conditions and, in particular, to the compression or expansion of the yield curve in the global bonds market. From this perspective, we empirically investigate whether the Twin Ds manifests in the data during such episodes, offering compelling evidence that this is the case.

In short, we add one ingredient to the contemporaneous narrative surrounding the Twin Ds, by postulating that changes in the slope of the yield curve, the term spread, serve as significant triggers of the phenomenon in the region. We specifically focus on the case of five Latin American markets: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico, examining how changes in the US term spread, a gauge of shifting expectations in global economic conditions, play a significant role in driving these twin risks.

Our empirical strategy employs the recently developed Quantile Vector Autoregressions (QVAR) framework to capture the nuanced impacts of US term spread changes on these markets. This approach allows for the estimation of directed and undirected relationships across the entire conditional distribution of the study variables, providing a more detailed understanding of risk spillovers that occur, particularly during extreme market conditions. The QVAR framework is adept at uncovering asymmetric spillover effects, which are crucial for understanding the impacts of global economic shifts on local markets.

In particular, we examine shocks corresponding to extremely high and low realizations of sovereign credit risk, substantial depreciation or appreciation risks, and significant stock market losses and gains. This enables us to distinguish between risk spillovers (occurring at the tails of the distributions) and pricing spillovers (located at the center of these distributions) and compare their magnitudes over time.

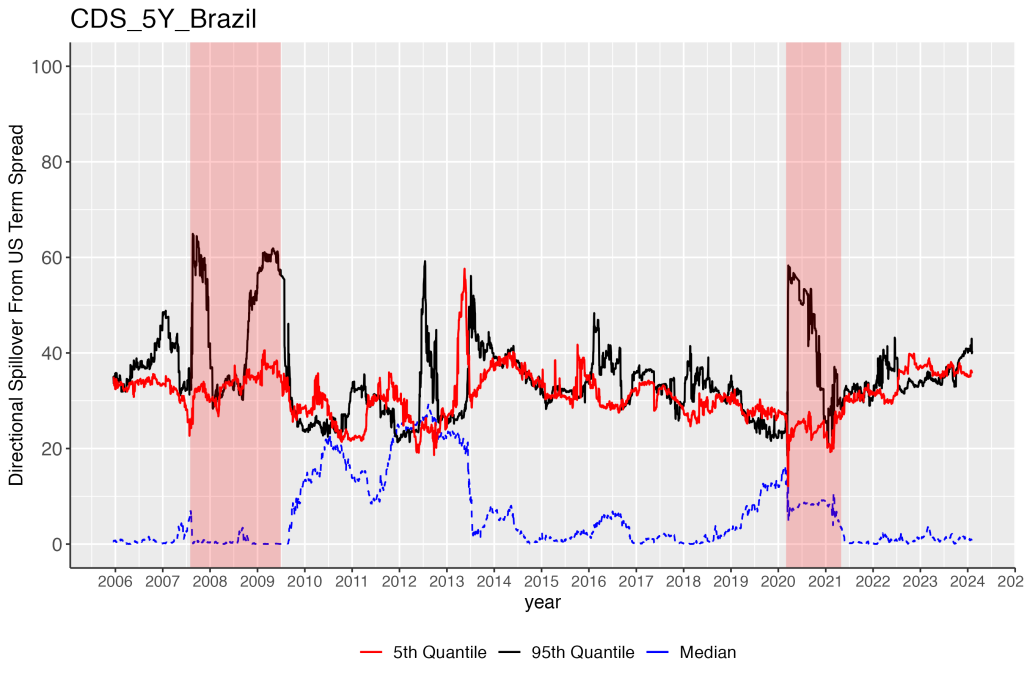

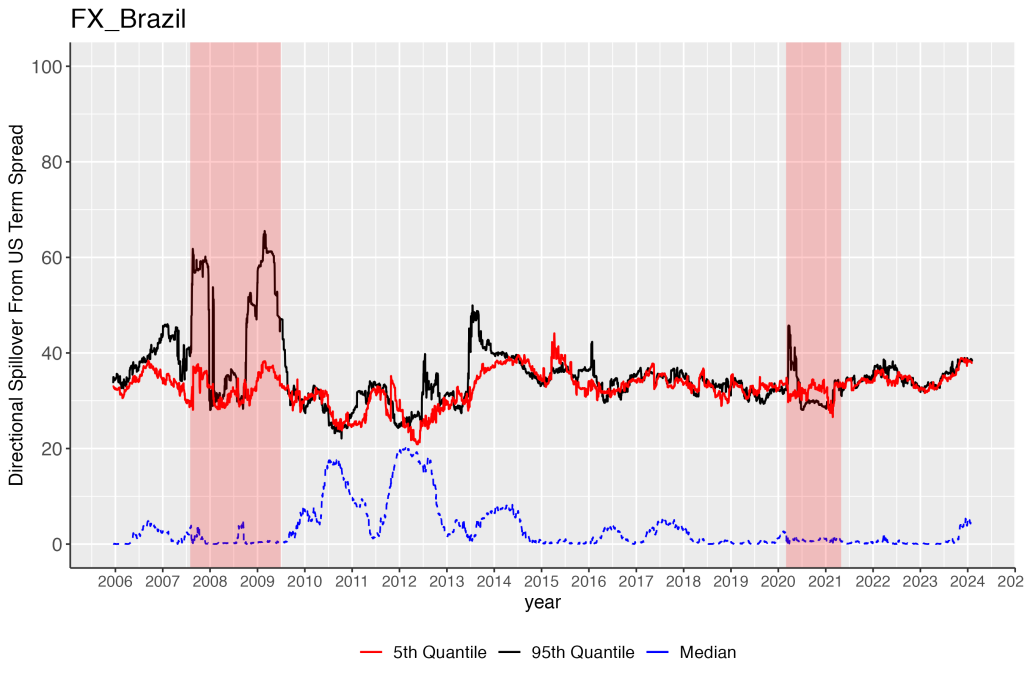

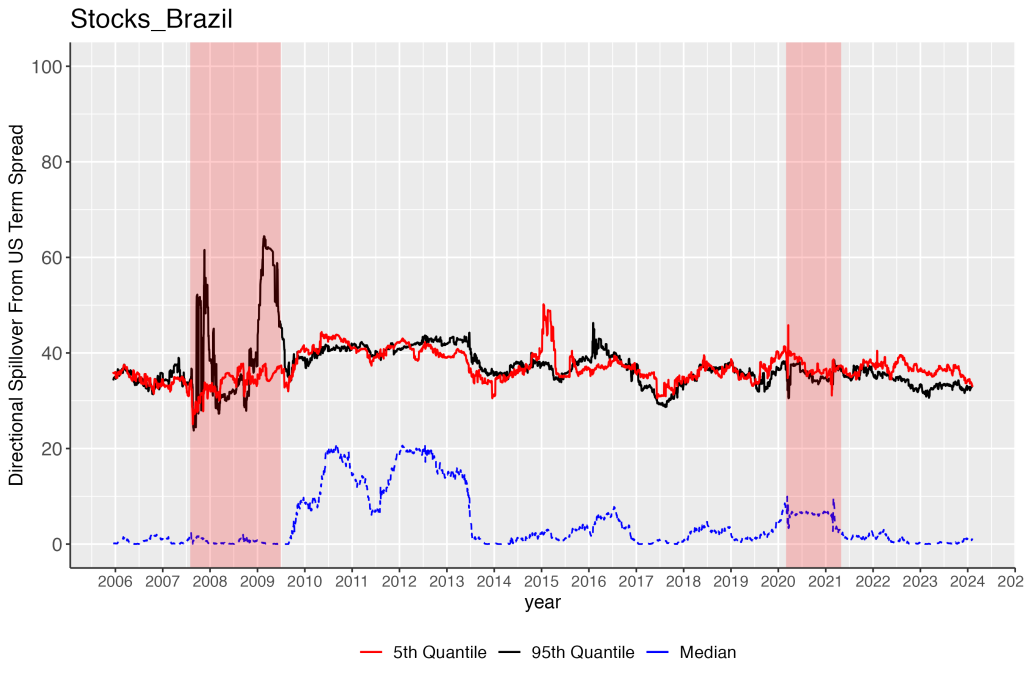

Figure 1 illustrates the time evolution of the spillover statistics, including spillovers to the stock markets, for the sake of comparison. The plots illustrate the directional spillover at the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles from the US Term Spread to sovereign credit default swaps, foreign exchange, and stock markets in Brazil as an example (you can check all countries in our working paper).

Figure 1. Directional Spillovers: Brazil

Our results reveal significant asymmetric spillover effects, particularly during periods of positive and increasing spreads, such as those observed during the Global Financial Crisis. The changes in the US term spread disproportionately impact the depreciation tail in currency markets and the high-risk tail in sovereign Credit Default Swaps (CDS) markets. Notably, these effects are absent in stock markets, highlighting the unique currency and sovereign debt market dynamics in response to global economic conditions.

In short, following our results, during periods of US dollar appreciation, typically characterized by a flight to quality and rising Term spreads, international investors tend to unwind their positions in less liquid currencies to invest in assets denominated in US dollars, which are perceived as safer and more liquid. As a result, spillovers in CDS and FX markets become more pronounced, leading to the manifestation of the Twin Ds phenomenon in the Latin American region.

For instance, in the event of a potential currency crisis that a Latin American market may encounter, after the realization of Term spread spillovers to the regions, currencies are more susceptible to depreciations than appreciations. Consequently, sovereign risk exposure also escalates, as CDS contracts would reflect a heightened risk of default on debt but also a simultaneous depreciation pressure coming from global markets.

The findings from this study underscore the necessity of incorporating risk spillovers into policy frameworks. As global economic conditions fluctuate, the impacts on sovereign credit risk and currency risk distributions in emerging markets can be profound. By acknowledging the dominance of risk spillovers over price spillovers and the obscured nature of shocks at the center of the variables’ distribution, policymakers can better formulate strategies to mitigate these risks.

Our study contributes to the broader discourse on the Twin Ds in emerging markets by highlighting how shifts in the US term spread serve as significant triggers of these phenomena. By analyzing the data during episodes of economic shocks, we provide compelling evidence that these risks are not merely localized concerns but are significantly influenced by global economic spillovers. This research not only enhances our understanding of the financial vulnerabilities of emerging markets but also assists policymakers and international investors in making informed decisions.

We encourage readers to delve deeper into our findings by reading the full paper in our web page, which provides a comprehensive analysis of the data and methodologies used.

References

Della Corte, P., Sarno, L., Schmeling, M., & Wagner, C. (2022). Exchange rates and sovereign risk. Management Science, 68(8), 5591-5617.

Bernoth, K., & Herwartz, H. (2021). Exchange rates, foreign currency exposure and sovereign risk. Journal of International Money and Finance, 117, 102454.

Na, S., Schmitt-Grohé, S., Uribe, M., & Yue, V. (2018). The twin ds: Optimal default and devaluation. American Economic Review, 108(7), 1773-1819.

Reinhart, C. M. (2002). Default, currency crises, and sovereign credit ratings. the world bank economic review, 16(2), 151-170.