Authors:

Carlos Giraldo, Latin American Reserve Fund, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: – cgiraldo@flar.net

Iader Giraldo, Latin American Reserve Fund, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: – igiraldo@flar.net

José E. Gómez-González, Department of Finance, Information Systems, and Economics, City University of New York – Lehman College, Bronx, NY, 10468, USA. Email: – jose.gomezgonzalez@lehman.cuny.edu

Jorge M. Uribe, Serra Húnter Fellow, Faculty of Economics and Business and IREA-Riskcenter, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain, Email: – jorge.uribe@ub.edu

In May 2007, during a period marked by significant capital inflows, rapid credit growth, and soaring real estate prices in Colombia, the central bank introduced an unprecedented macroprudential measure that any other country had not adopted. This policy established a cap on the Posición Bruta de Apalancamiento (PBA), i.e., Gross Leverage Position in Foreign Exchange Derivatives, which limited the ratio of a bank’s gross exposure in foreign exchange derivatives to its capital. While facing opposition from the banking association, the central bank argued that the PBA was necessary to mitigate the credit risk exposure of Colombian banks and protect the stability of the financial system. Consequently, a 500% limit on the PBA was implemented, effective May 6, 2007. The primary goal of this policy was to slow down the rapid credit growth that central bank officials believed could lead to financial imbalances and housing market bubbles.

This blog post shares the story behind our recent working paper on how Colombia’s unique Gross Leverage Position in foreign exchange derivatives helped prevent a housing bubble from bursting and what emerging economies can learn from it.

While Colombia had previously enacted taxes on foreign debt and portfolio investments—measures similar to those introduced in Brazil and Chile—this cap on the Posición Bruta de Apalancamiento, or Gross Leverage Position in Foreign Exchange Derivatives, was distinctive to Colombia. No other country had ever adopted such a policy. The measure was announced and implemented without prior notice to banks. Given the unexpected nature of the measure, its unique character, and its specific application in Colombia at a particular point in time, it serves as an ideal case for studying its effectiveness as a macroprudential policy.

Housing prices are among the most crucial determinants of a country’s financial and macroeconomic stability. As a key macroeconomic indicator, they significantly influence both consumption and investment, shaping economic and financial cycles. Given that housing represents a substantial share of household wealth, price fluctuations have far-reaching effects on consumption, savings, and labor market decisions.

Moreover, housing prices play a critical role in investment, particularly within the real estate sector, which is a leading indicator of future economic activity. Real estate assets, including housing, also serve as essential collateral for bank loans, exerting considerable influence on credit expansion. When housing prices rise, the value of collateral increases, enabling greater lending activity and fueling economic growth. However, excessive credit growth driven by rising property values can also heighten financial vulnerabilities. As Schularick and Taylor (2012) demonstrated, the interplay between credit expansion and housing price appreciation is a key determinant of financial stability, with sharp increases in both variables significantly increasing the probability of financial crises.

Given the destabilizing effects that excessive credit growth and surging housing prices can have on the economy, many countries have introduced macroprudential measures to restrain these dynamics and strengthen financial and macroeconomic stability. In small, open emerging economies such as those in Latin America, capital flow fluctuations play a pivotal role in shaping housing price and credit cycles.

The PBA, a macroprudential policy tool, was introduced by the Central Bank of Colombia during a phase of rapid credit expansion driven by significant capital inflows, which had inflated asset prices, including housing prices. Although some capital inflows were countered by capital controls instituted in 2006, Colombian banks continued to replicate foreign credit through local currency loans and foreign currency swaps. The PBA aimed to limit the capacity of Colombian banks to create synthetic foreign debt instruments, thereby reducing their exposure to foreign credit risks.

By curtailing the use of derivative markets to replicate foreign credit, the PBA ensures that bank credit growth remains consistent with the capital levels of banks. This regulatory approach reflects the current stance of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on capital flow management measures and macroprudential policies, which advocate for enhanced flexibility for countries to implement tools that span both categories. According to the IMF, these measures can aid countries in managing capital inflows and mitigating risks to financial stability, not only during capital flow surges but also in more stable periods (Biljanovska et al., 2023).

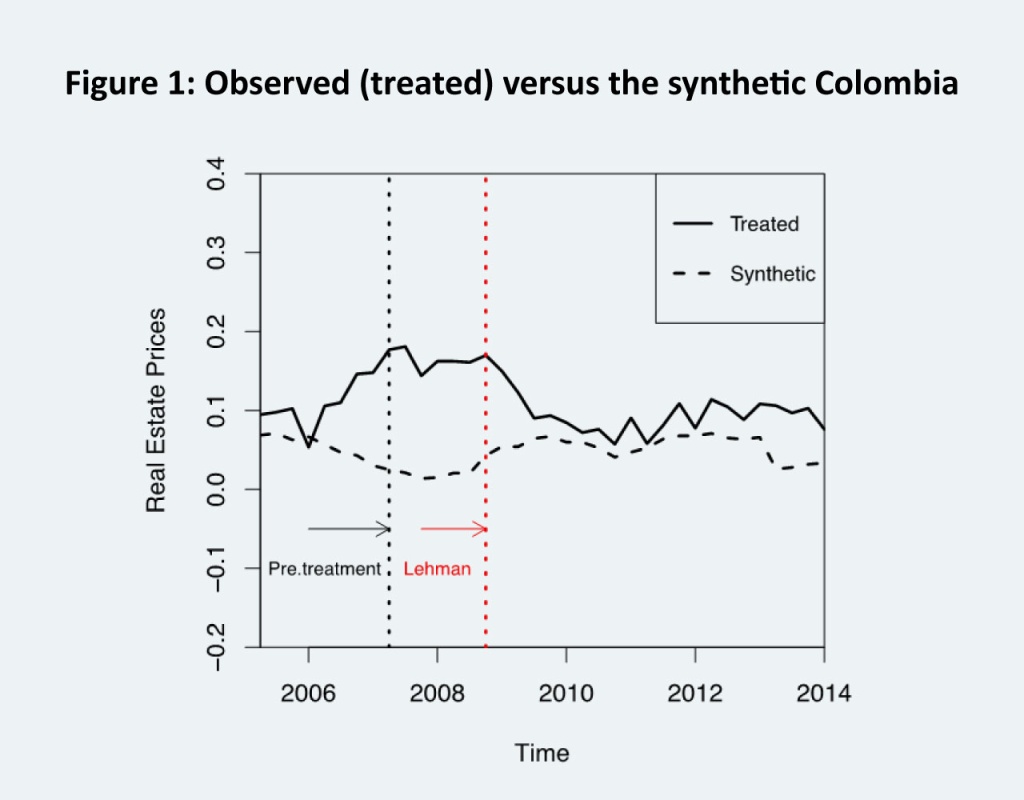

Our study reveals that the implementation of the PBA significantly reduced the rate of housing price growth in Colombia (Figure 1). Notably, this policy initiated a trend reversal, leading to a gradual decline in the rate of increase after it had been positive and accelerating prior to the introduction of the PBA. We substantiate this causal effect by comparing housing price growth in Colombia to a synthetic counterfactual. After the PBA was implemented, the gap in housing price growth between Colombia and synthetic Colombia narrowed, particularly following the Global Financial Crisis, resulting in near-total convergence. This finding demonstrates the PBA’s effectiveness as a macroprudential measure, especially in periods of financial instability. By stabilizing housing prices and preventing asset bubbles, the PBA enhances financial resilience and helps institutions withstand external shocks, thus reinforcing economic stability and investor confidence.

Our findings are bolstered by placebo tests, which validate the identified impact. Our research enhances our understanding of how macroprudential measures influence housing prices during periods of rapid expansion, and it provides valuable insights for the effective implementation of such policies in small, open economies where credit dynamics and housing prices are heavily influenced by international capital flows. Ultimately, our results suggest that policies such as the PBA are effective in moderating housing price growth during surges, serving as a crucial complement to more traditional measures such as the loan-to-value (LTV) and loan-to-income (LTI).

Several policy implications can be derived from these findings. First, the PBA provides a valuable case study for other emerging economies facing similar challenges with housing market dynamics and credit expansion. Policymakers can learn from Colombia’s experience and implement innovative macroprudential measures tailored to their unique economic and financial contexts. Second, our study underscores the importance of understanding the timing and context of policy implementation, as the PBA’s success in curbing housing price growth during an economic downturn emphasizes the need for policymakers to remain responsive to changing market conditions and ensure macroprudential measures effectively address emerging vulnerabilities. Finally, future research should examine the long-term effects of the PBA and similar policies on economic growth, productivity, and housing market dynamics, which will be crucial for refining macroprudential frameworks and enhancing the resilience of financial systems while considering ongoing global economic challenges.

References

Biljanovska, N., Chen, S., Gelos, M. R., Gelos, R., Igan, D., Igan, M. D. O., … & Valencia, M. F. (2023). Macroprudential Policy Effects: Evidence and Open Questions. International Monetary Fund.

Schularick, M., & Taylor, A. M. (2012). Credit booms gone bust: monetary policy, leverage cycles, and financial crises, 1870–2008. American Economic Review, 102(2), 1029-1061.