Authors:

Carlos Giraldo, Latin American Reserve Fund, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: – cgiraldo@flar.net

Iader Giraldo, Latin American Reserve Fund, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: – igiraldo@flar.net

Jose E. Gomez-Gonzalez, Department of Finance, Information Systems, and Economics, City University of New York – Lehman College, Bronx, NY, 10468, USA. Email: – jose.gomezgonzalez@lehman.cuny.edu

Jorge M. Uribe, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, Email: – jorge.uribe@ub.edu

Housing affordability has traditionally been analyzed through a macro-financial lens. Credit conditions, income growth, interest rates, and speculative dynamics have dominated the debate around housing prices and their divergence from fundamentals. Yet, as climate change accelerates, a new structural driver is becoming increasingly relevant for urban real estate markets: climate risk and climate-related amenities.

Our recent working paper, “Climate Hazards Meet Overpriced Cities: Linking Environmental Risks to Real Estate Markets Across the Globe”, explores how climate hazards affect housing affordability across a global sample of cities, focusing on the price-to-income (PTI) ratio as a measure of overvaluation and social stress in housing markets. Our research introduces a novel perspective by showing that climate factors matter little for “typical” housing markets but become highly influential in the most overpriced cities worldwide.

The determinants of the price-to-income (PTI) ratio in urban real estate markets have been extensively examined in the literature. Most studies focus on credit conditions and systemic risk, treating the PTI ratio primarily as a measure of housing affordability. The underlying premise is that housing prices cannot diverge indefinitely from the income levels of potential buyers. If prices consistently outpace income growth, households will eventually be unable to purchase homes, reducing demand and exerting downward pressure on prices (André et al., 2014).

Households generally choose between owning and renting, and this decision depends on the relative levels of house prices and rents. When prices rise faster than rents, renting becomes more attractive, easing pressure on housing prices while putting upward pressure on rents, and vice versa. Persistent deviations from these dynamics, such as those documented by André et al. (2014), raise concerns about social inequality, as vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected by the reduced affordability that accompanies rising housing prices.

The relationship between PTI ratios and climate risks remains far less understood. While a considerable body of research has examined how environmental amenities and climate-related hazards influence housing prices, the direct link to the PTI ratio has received only limited attention. Our study examines, for the first time, the determinants of PTI ratios in relation to climate risk. While earlier work identifies channels linking climate factors to housing outcomes, it largely focuses on single countries, metropolitan areas, or narrowly defined hazards, leaving an incomplete understanding of how affordability ratios vary across a broad cross-section of cities worldwide. Moreover, most previous research focuses on housing prices rather than the PTI ratio itself, and none of these studies consider how the effects of climate hazards may be concentrated at the extremes of the affordability distribution.

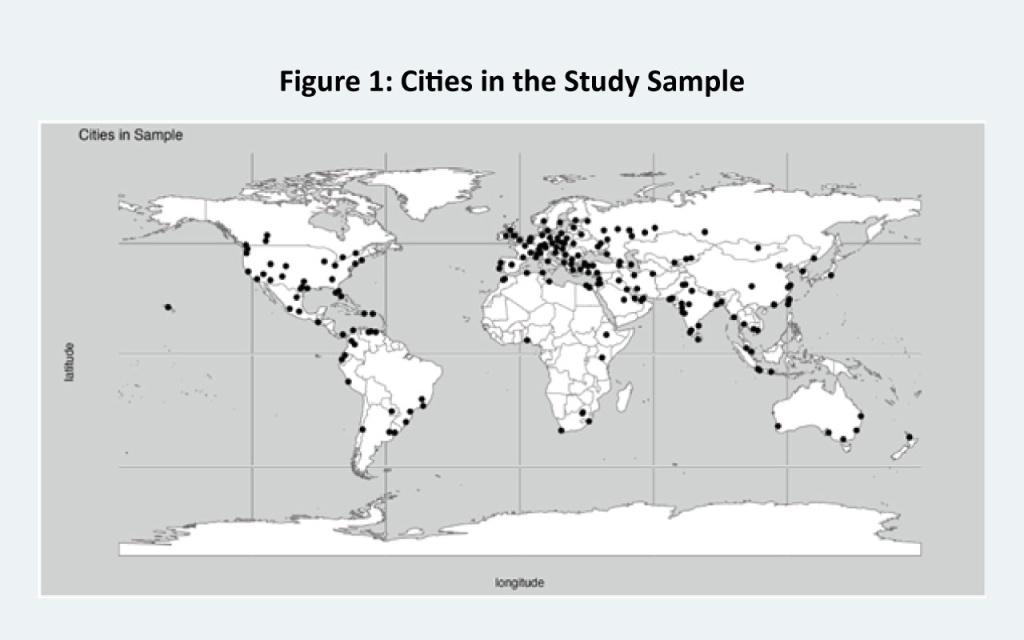

Our study combines climate data with city-level PTI ratios, covering 195 cities across world. Our results show that the dynamics of the most overpriced housing markets worldwide differ markedly from those of more typical markets. In cities at the right tail of the PTI distribution, both climate risks and climate-related weather amenities are capitalized into housing prices. Specifically, higher values of cooling degree days are associated with increases in PTI ratios at the upper quantiles, whereas extreme temperatures are linked to decreases in PTI ratios. Taken together, these findings reveal new social gaps to be expected from climate change; they suggest that overpricing is likely to intensify in regions where moderate temperature increases raise the amenity value of climate change—provided that these cities are not highly exposed to other climate hazards. In contrast, tropical cities, where temperatures already approach physiological and comfort limits and where climate risks are more acute, may experience declining PTI ratios as extreme heat reduces housing demand, thereby easing affordability pressures.

Our study provides fresh evidence on the role of climate risk in shaping housing affordability across a large global sample of cities. Using hierarchical clustering and quantile regression, we show that climate hazards have negligible effects on PTI ratios in typical housing markets but become highly significant in the most overpriced ones. Prolonged warming, captured by cooling degree days, is associated with higher PTI ratios at the upper end of the distribution, reflecting the amenity value of milder winters and warmer conditions. In contrast, extreme heat events, as measured by the number of days exceeding 35 °C, are linked to lower PTI ratios in high-PTI markets, suggesting that acute heat stress can dampen demand and partially counteract housing overvaluation.

Our findings highlight the dual nature of climate change as both an amenity and a risk. Cities experiencing moderate warming that enhances comfort, particularly during the winter, may see housing markets become even less affordable as climate change progresses. Conversely, cities already exposed to high baseline temperatures and frequent extreme heat events are likely to face downward pressure on PTI ratios as housing demand weakens, potentially improving affordability but at the cost of higher social, demographic, and health risks.

The policy implications of our results vary. In high-income or temperate cities where warmer winters may further inflate PTI ratios -such as Paris, Lisbon, or Seoul- policy-makers should prepare for worsening affordability pressures by expanding the supply of affordable housing, changing zoning to allow higher-density development, and considering climate-sensitive property taxation to curb speculative demand. Financial regulators and lenders should incorporate differentiated climate signals into property valuation and mortgage underwriting to avoid fueling bubbles in markets where warming-related amenities drive overpricing. Infrastructure planning in these markets should also anticipate higher energy demand and cooling needs to prevent future supply bottlenecks.

In contrast, tropical and already hot cities, such as Jakarta, Bangkok, or Addis Ababa, are more likely to experience reduced overpricing but face serious societal challenges from extreme heat, including rising mortality, deteriorating public health, and climate-induced migration. For these cities, policy priorities should focus less on climate change-related affordability and more on adaptive strategies, such as investing in green infrastructure, cooling centers, and heat-resilient urban planning to maintain livability. At the national and regional levels, governments should develop early warning systems to monitor PTI dynamics, prepare for possible migration flows from heat-stressed areas, and coordinate housing and infrastructure investments accordingly.

Climate change is not only an environmental challenge; it is also a financial stability issue. By showing that climate risks primarily affect the most overpriced cities, this research identifies a new channel through which climate change can deepen urban inequalities and macro-financial risks. Addressing these challenges will require policies that integrate urban economics, climate adaptation, and financial regulation, tailored to each city’s specific conditions.

References

André, C., Gil-Alana, L. A., & Gupta, R. (2014). Testing for persistence in housing price-to-income and price-to-rent ratios in 16 OECD countries. Applied Economics, 46(18), 2127-2138