Authors:

Carlos Giraldo, Latin American Reserve Fund, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: – cgiraldo@flar.net

Iader Giraldo, Latin American Reserve Fund, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: – igiraldo@flar.net

Jose E. Gomez-Gonzalez, Department of Finance, Information Systems, and Economics, City University of New York – Lehman College, Bronx, NY, 10468, USA. Email: – jose.gomezgonzalez@lehman.cuny.edu

Jorge M. Uribe, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, Email: – jorge.uribe@ub.edu

Capital acts as a safeguard that enables banks to endure shocks that might otherwise trigger distress episodes. The level of capital a bank maintains shapes its incentives to manage risks responsibly and determines its capacity to absorb losses during adverse economic conditions.

From a theoretical perspective, two main views discuss the effects of bank capitalization: one holds that stronger capital improves banks’ asset selection discipline and borrower monitoring (Holmstrom and Tirole, 1997), while related studies suggest it promotes long-term growth via expanded lending, liquidity creation, and stronger competition (Allen et al., 2011; Berger and Bouwman, 2013; Mehran and Thakor, 2011); conversely, higher capital may restrict liquidity and intermediation services, causing contracting inefficiencies and less liquidity creation (Diamond and Rajan, 2001), and prompt greater risk-taking (Acosta-Smith et al., 2024). Yet both views agree that higher capital ratios make banks less fragile.

This lesson became particularly evident following the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009, which Thakor identifies as fundamentally a solvency crisis (Thakor, 2014). If this prevailing view holds, one could argue that the GFC might have been prevented through higher bank capital requirements. Moreover, recent empirical evidence shows that higher capital requirements, while reducing lending in the short term, promote safer lending standards in the medium term, with limited downside effects on the economy (Cappelletti et al., 2024).

To address bank capital’s inherent procyclicality, Basel III and its revisions introduced tools like the countercyclical capital buffer. These measures raise requirements during economic expansions, when risks build up unnoticed, and relax them during downturns to sustain credit flows, especially to constrained borrowers like SMEs. Regulators thereby aim to accumulate capital in good times for drawdown in bad times, smoothing the credit cycle and reducing systemic vulnerabilities.

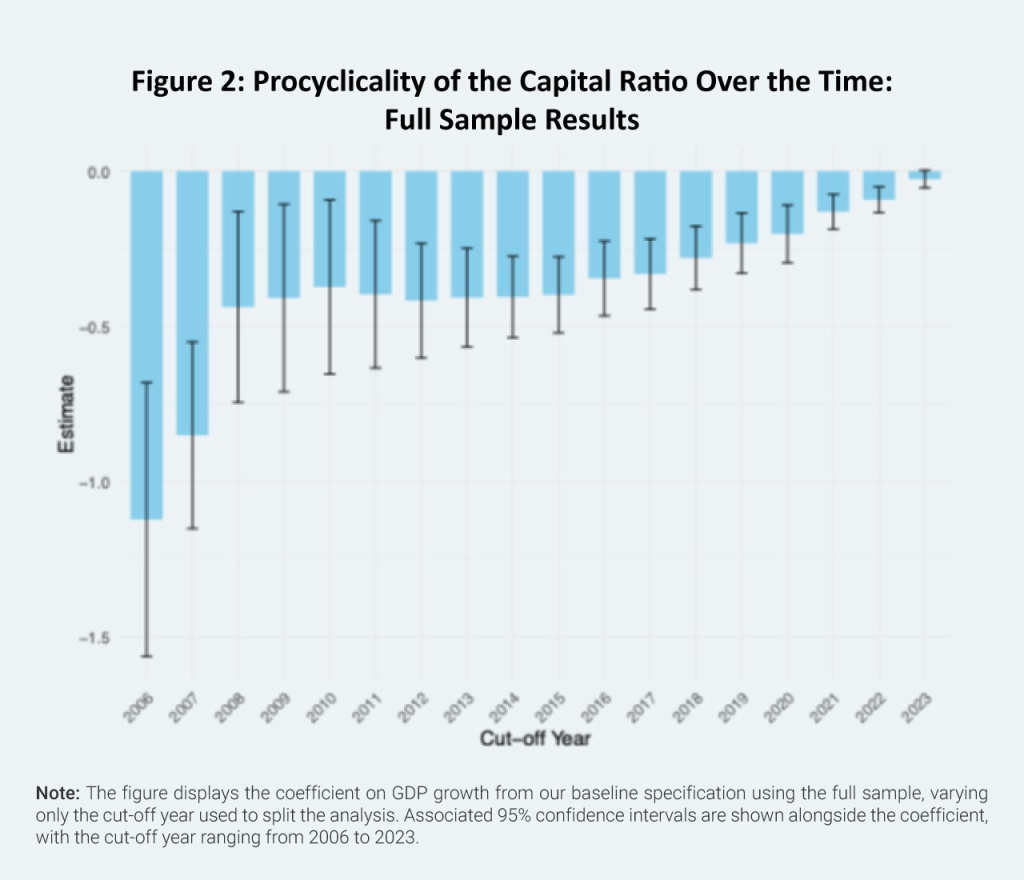

From a macroprudential perspective, this suggests the traditional negative association between bank capital and economic growth should have weakened or even reversed in recent years. Our recent study, Disappearance of Bank Capital Pro-Cyclicality in Emerging and Low-Income Economies under Basel III, examines this question directly. In our empirical models, we focus on simple capital ratios rather than risk-weighted measures, following recent evidence that the Basel III leverage ratio exhibits a more countercyclical profile than risk-weighted counterparts.

Our focus is on emerging market economies, where empirical evidence remains scarce, particularly in the post–Basel III period. We use a large panel of banks (1,185 in total) across a broad set of emerging and low-income countries (122 in total) from 2004 to 2024 to examine the cyclicality of capital ratios, with a particular focus on how this relationship has evolved over the past decade—a period marked by significant transformations in the global financial safety net.

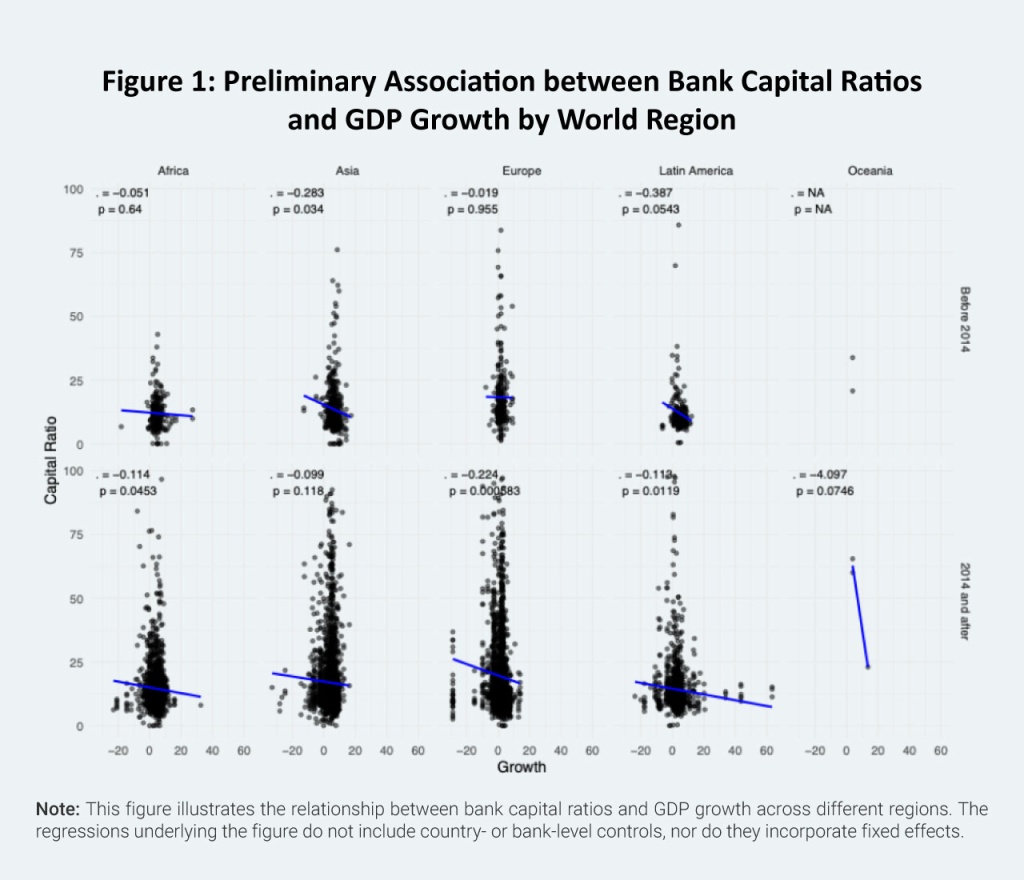

In general terms, we confirm that, prior to 2014, capital ratios were predominantly procyclical, but this relationship has reversed over the past decade. Our results, however, exhibit considerable heterogeneity across world regions. Among non-advanced economies, Latin America and the Caribbean as well as Developing Asia and the Middle East have shown the greatest progress in moderating procyclicality. By contrast, Central and Eastern Europe and Sub-Saharan/North Africa countries show less improvement. In the case of Central and Eastern Europe, capital ratios were largely acyclical even before 2014, limiting observable changes, while in Sub-Saharan and North Africa, progress has been confined to a smaller subset of institutions, conditional on the initial level of the capital ratio.

We also find that banks with higher capital ratios are indeed less sensitive to the business cycle and, in some regions, even become countercyclical in the latter half of the sample. Additionally, we document novel evidence showing that bank equity as a proportion of total assets exhibits substantial heterogeneity in its response to both bank-level and country-level determinants, consistent with expectations that better-capitalized banks can respond more effectively to internal and external shocks.

Overall, our findings point to several policy implications of practical relevance. The reduced procyclicality of capital ratios in many emerging economies suggests that the principles underlying modern macroprudential regulation, particularly the idea of accumulating capital in good times to preserve credit flows in downturns, may already be influencing bank behavior even where Basel III has not been formally implemented. The pronounced regional heterogeneity in our results shows that this progress remains uneven. Differences in the depth and timing of Basel III implementation appear to shape how banks adjust their capital buffers over time. These patterns underscore the value of more effective supervisory frameworks supported by the global safety net, closer scrutiny of internal risk-weighting practices, and a stronger capacity to deploy countercyclical capital instruments in jurisdictions where procyclical behavior remains entrenched.

The evidence that better-capitalized banks behave more countercyclically reinforces the case for higher capital requirements, both because they enhance individual bank resilience and because they help stabilize aggregate credit conditions during periods of stress. Taken together, these results support a more proactive regulatory stance and suggest that further strengthening of macroprudential frameworks could yield significant benefits in reducing the amplitude of credit cycles and mitigating the social costs of financial instability.

References

Acosta-Smith, J., Grill, M., & Lang, J. H. (2024). The leverage ratio, risk-taking and bank stability. Journal of Financial Stability, 74, 100833.

Allen, F., Cadetti, E., & Marquez, R. (2011). Credit market competition and capital regulation. Review of Financial Studies, 24, 983–1018.

Berger, A., & Bouwman, C. (2013). How does capital affect bank performance during financial crises? Journal of Financial Economics, 109(1), 146–176.

Cappelletti, G., Marques, A. P., & Varraso, P. (2024). Impact of higher capital buffers on banks’ lending and risk-taking in the short- and medium-term: Evidence from the euro area experiments. Journal of Financial Stability, 72.

Diamond, D., & Rajan, R. (2001). Liquidity risk, liquidity creation, and financial fragility. Journal of Political Economy, 109, 278–327.

Holmstrom, B., & Tirole, J. (1997). Financial intermediation, loanable funds, and the real sector. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(3), 663-691

Mehran, H., & Thakor, A. (2011). Bank capital and value in the cross-section. Review of Financial Studies, 24, 1019–1067.

Thakor, A. V. (2014). Bank capital and financial stability: An economic trade-off or a Faustian bargain? Annual Review of Financial Economics, 6, 185–223.